Editor, Webmaster: Phil Cartwright Editor@earlyjas.org

|

| Earlville Association for Ragtime Lovers Yearning for Jazz Advancement and Socialization |

EARLYJAS

Jazz, America’s original art form, has found its way into virtually every corner of the world. With

radio, television, commercially recorded music and the Internet it is available 24/7/365 to all with the

means to receive or purchase it. But, as jazz started and expanded, these sources were not available, so its

initial introduction – before the wide-spread popularity of 78 records - was up close and personal: traveling

musicians, including members of the U. S. Army.

1914 saw the beginning of The Great War, The War to End All Wars, or finally World War I. It ended

in 1918, a devastating event which caused the deaths of over 17 million souls, military and civilian, and

forever changed life. It was an event to change America as well, with four million military personnel

mobilized, as well as the services of organizations such as the Red Cross, YMCA, American Field Service,

Knights of Columbus and other charitable entities.

By 1914, and up until America’s entry into the War in 1917, jazz had started to prosper and spread.

Musicians started to leave New Orleans: Freddie Keppard showed up in Los Angeles, Tom Brown’s Band

From Dixieland was playing in Chicago. That band morphed into The Original Dixieland Jass Band, which

is credited with cutting the first jazz record in 1917: “Livery Stable Blues” and “The Original Dixieland

One-Step” on Victor.

New song titles appeared almost daily: “Darktown Strutters’ Ball,” “Hot House Rag,” “St. Louis

Blues,” “Yellow Dog Blues,” “Bill Bailey,” “Ballin’ The Jack,” “That’s A Plenty,” “Weary Blues,” “Beale

St. Blues,” “Tiger Rag,” “Shim-Me-Sha-Wabble,” and many other songs familiar even today. In 1914

Prince’s Orchestra had a hit record of “Ballin’ the Jack;” in 1916 Wilbur C. Sweatman released “Down

Home Rag.”

African-American composers and artists were also featured: James Reese Europe and his Clef Club

Orchestra gave their first Carnegie Hall concert in 1912; Scott Joplin’s ragtime opera, “Treemonisha,” was

performed in 1915. Earlier, in 1908, New York City enjoyed Williams’ & Walker’s production of

“Bandana Land,” with music by Will Marion Cook; it ran for 89 performances at the Majestic Theater on

Columbus Circle.

More and more Americans were hearing jazz and rag-time, and some musicians were even traveling

overseas, primarily to England. However, the war put a real damper on any meaningful expansion of jazz,

or what is often called proto-jazz, in Europe. Enter the U. S. Army.

On April 2, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson addressed congress and asked for a declaration of war

against Germany; on April 4, his request was granted. Many men and women of musical talent were

among those who volunteered or were drafted. Those people were familiar with the new, popular styles of

music in America and were skilled players or singers. Their collective task was to win the war – and they

did. With war’s end, the celebrations started, and so did the music.

There are several military aggregations that stand out at this point in time, and they are among those

credited with helping to introduce Europe to jazz. Many of us are well aware of the efforts of the USO

during WWII to entertain the troops. Less well-known is the major effort performed in WWI Europe by

America’s superstars of the day. That is another big story, but the troops so entertained were certainly up-

to-date with current popular music.

The recording industry had prospered, even in Europe, and some of these aggregations were able to cut

sides there. One of them – the subject of this article – was a group known on their French recordings as

“L’Orchestre Scrap Iron Jazzerinos,” which cut ten sides for Pathé and Victor in Paris in late 1918 and

1919.

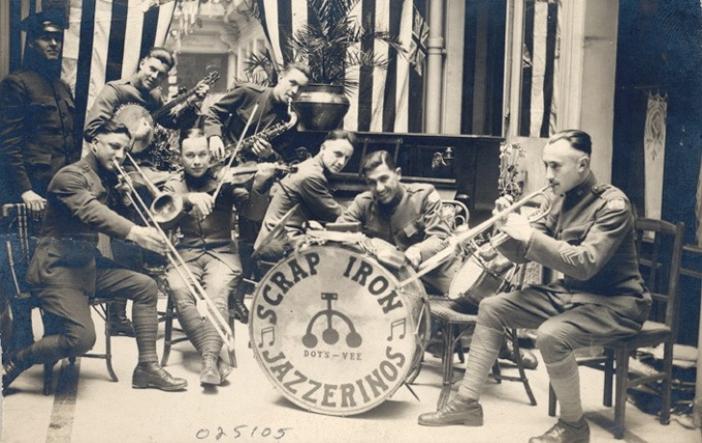

The Jazzerinos were all members of Base Hospital 21, located in Rouen, France. The hospital was

originally started by the Red Cross in the British sector, then turned over to the U.S. Medical Corps when

America entered the war. They were part of the U. S. II Corps, with the bulk of the personnel from the

Washington University Medical School in St. Louis, MO, although there were also members of Lakeside

Unit No. 4 from Cleveland, OH. The members of the band were Arshav Nushan, drums, Edwin Dakin,

violin, Syl Horn, banjo, Clarence Koch, trumpet, Russell Hauslaib, C-melody sax, Clayton Thirkell, piano

and Albert Angelotta, trombone. The Clevelanders were: Hauslaib, Thirkell and Angelotta. A close look at

the patch on Koch’s shoulder confirms that they were attached to the II Corps. (photo)

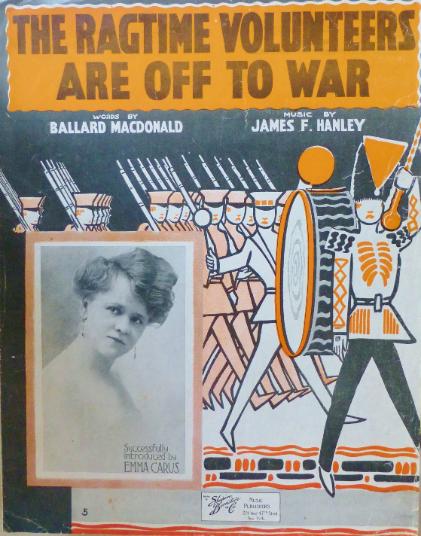

The tunes they recorded were: “Oh! How I Hate to Get Up in the Morning;” “Way Down in Macon,

Georgia;” “A.M.E.R.I.C.A. I Love You, My Yankee Land;” “The Pickanninie’s Paradise;” “The Ragtime

Volunteers Are Off to War;” “It’s A Hundred to One You’re In Love “N Everything;” “Sinbad;”

Everything Is Peaches Down in Georgia;” “How Ya Gonna Keep ‘Em Down on the Farm;” “Oh! So

Pretty;” “Sweet Little Buttercup et My Mother’s Eyes;” “Oui, Oui, Marie;” “I Ain’t Got Nobody,” and

“The Dirty Dozen.”

The selections seem typical for the times, except for the “Dozens.” That is the first published version

of an old black insult game, and far closer to the jazz idiom than most of the others, written and published

in 1917 by Clarence M. Jones, a black composer and pianist and rarely recorded. Two of the Jazzerino

sides may be heard on the Red Hot Jazz website.

They were popular. The Jazzerinos stayed in Europe after the war ended, played for YMCAs all over

Europe, the Versailles Peace Conference, the Queen of Romania and appeared at the Casino de Paris.

Appearing with them were such notables as Maurice Chevalier, Bob Carleton, composer of “Ja-Da” and

John Boles, movie actor and singer. As one can imagine, entertainment was the order of the day after four

years of horror, and American Army talents such as the Jazzerinos appeared often and to acclaim. They

helped bring jazz to Europe.

Copyright Brooke Anderson 2014