Editor, Webmaster: Phil Cartwright

Editor@earlyjas.org

Editor@earlyjas.org

|

Additions, comments, corrections, contributions

to Eric Seddon % Earlyjas, or e-mail:

eric.seddon@gmail.com

to Eric Seddon % Earlyjas, or e-mail:

eric.seddon@gmail.com

| Earlville Association for Ragtime Lovers Yearning for Jazz Advancement and Socialization |

EARLYJAS

Among the more recent books written by jazz clarinetists is an extremely important

memoir by Tom Sancton: New Orleans native, a Paris Bureau chief for Time

magazine, and trad jazz clarinetist.

and White (Other Press, New York, 2006). Beginning with the New Orleans jazz

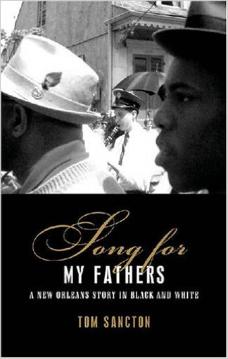

Sancton’s book is entitled Song for My Fathers: A New Orleans Story in Black

funeral of Doc Celestin on December 18, 1954, we’re given more than a glimpse

into a crucial two decades of Crescent City history, unfolding through the eyes of

young Tom Sancton. Son of a reporter and aspiring novelist, whose mother was a

southern belle, he is thrown into the world of Creole and black jazz musicians

during the foundation of Preservation Hall. His perspective is unique: a white kid

in that milieu, at a point in time that will never be repeated—when musicians like

George Lewis, Creole George Guesnon & Sweet Emma Barrett pioneered the

early jazz revival.

The book is masterful, combining many genres seamlessly. A coming of age story,

a chronicle, an analysis of oral tradition music making, with the flair and page-

turning quality of a novel, this is simply one of the best books about jazz, and

about New Orleans, I’ve ever read. Through much of it, Sancton’s adolescence on

display as he learns to play clarinet, falls in love for the first time, and tries to

balance his passion for jazz with school and other obligations. We overhear him

taking music lessons from Lewis and Guesnon; in the process becoming privy to

their struggles, ambivalences, and hesitations, as they were finally showcased and

given a share of success for the music they helped pioneer and preserve.

Throughout the book, the figure of his father looms large: the younger Sancton’s

admiration, then disillusionment, with his father is skillfully and poignantly told,

settling into a sober middle aged reassessment. None of this interferes with the

musical aspect of the story—instead, like the quality of New Orleans jazz itself,

Sancton’s life and the music become inseparable.

Like Sidney Bechet’s autobiography, this written demonstration of the life

becoming the music, and the two flowing in and out of each other, is the most

remarkable aspect of the book. Anyone who seriously involves themselves with

New Orleans jazz must eventually come to this conclusion: It is the life one lives,

and the depth of one’s soul, that must come through the music. There is no faking

it. And Tom Sancton fakes nothing: You can smell the Zatarain’s, feel the

humidity, taste the danger of bullets being thrown during a parade, get lost in the

tunes—you can experience with him a type of hero worship turning bitter, then

mellowed, then resolving into something like pure gratitude. I picked this volume

up on the recommendation of a friend from NOLA, and at first wasn’t so sure

what to think. It ended up giving me a far deeper appreciation of music, life, and

the relationship of the two. - - Eric Seddon

memoir by Tom Sancton: New Orleans native, a Paris Bureau chief for Time

magazine, and trad jazz clarinetist.

and White (Other Press, New York, 2006). Beginning with the New Orleans jazz

Sancton’s book is entitled Song for My Fathers: A New Orleans Story in Black

funeral of Doc Celestin on December 18, 1954, we’re given more than a glimpse

into a crucial two decades of Crescent City history, unfolding through the eyes of

young Tom Sancton. Son of a reporter and aspiring novelist, whose mother was a

southern belle, he is thrown into the world of Creole and black jazz musicians

during the foundation of Preservation Hall. His perspective is unique: a white kid

in that milieu, at a point in time that will never be repeated—when musicians like

George Lewis, Creole George Guesnon & Sweet Emma Barrett pioneered the

early jazz revival.

The book is masterful, combining many genres seamlessly. A coming of age story,

a chronicle, an analysis of oral tradition music making, with the flair and page-

turning quality of a novel, this is simply one of the best books about jazz, and

about New Orleans, I’ve ever read. Through much of it, Sancton’s adolescence on

display as he learns to play clarinet, falls in love for the first time, and tries to

balance his passion for jazz with school and other obligations. We overhear him

taking music lessons from Lewis and Guesnon; in the process becoming privy to

their struggles, ambivalences, and hesitations, as they were finally showcased and

given a share of success for the music they helped pioneer and preserve.

Throughout the book, the figure of his father looms large: the younger Sancton’s

admiration, then disillusionment, with his father is skillfully and poignantly told,

settling into a sober middle aged reassessment. None of this interferes with the

musical aspect of the story—instead, like the quality of New Orleans jazz itself,

Sancton’s life and the music become inseparable.

Like Sidney Bechet’s autobiography, this written demonstration of the life

becoming the music, and the two flowing in and out of each other, is the most

remarkable aspect of the book. Anyone who seriously involves themselves with

New Orleans jazz must eventually come to this conclusion: It is the life one lives,

and the depth of one’s soul, that must come through the music. There is no faking

it. And Tom Sancton fakes nothing: You can smell the Zatarain’s, feel the

humidity, taste the danger of bullets being thrown during a parade, get lost in the

tunes—you can experience with him a type of hero worship turning bitter, then

mellowed, then resolving into something like pure gratitude. I picked this volume

up on the recommendation of a friend from NOLA, and at first wasn’t so sure

what to think. It ended up giving me a far deeper appreciation of music, life, and

the relationship of the two. - - Eric Seddon

Tom Sancton autobiography:

Song for my Fathers: A New Orleans

Story in Black and White

Jazz clarinetists are particularly fortunate

when it comes to autobiographies.

Contributions to the genre include some of

the most important players in the history of

the instrument: Benny Goodman, Artie

Shaw, Barney Bigard, Woody Herman, Pete

Fountain, and Mezz Mezzrow have each

published volumes, and at least one of them

- Sidney Bechet’s Treat It Gentle - ought to

be considered a masterpiece of American

literature in its own right.

Song for my Fathers: A New Orleans

Story in Black and White

Jazz clarinetists are particularly fortunate

when it comes to autobiographies.

Contributions to the genre include some of

the most important players in the history of

the instrument: Benny Goodman, Artie

Shaw, Barney Bigard, Woody Herman, Pete

Fountain, and Mezz Mezzrow have each

published volumes, and at least one of them

- Sidney Bechet’s Treat It Gentle - ought to

be considered a masterpiece of American

literature in its own right.