BOOK REVIEW

by Bert Thompson

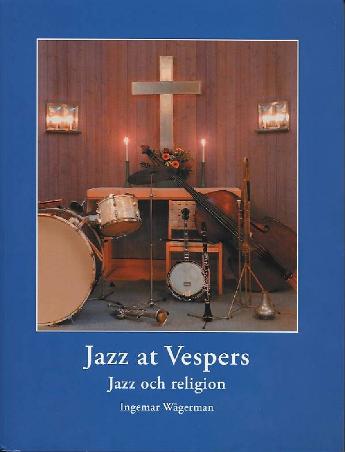

Jazz at Vespers: Jazz and religion

By Ingemar Wågerman

Hönö, Sweden, self-published, 197pp ISBN 978-91-637-2274-5 paperback

[Note: The print version of this book is in Swedish only, but for the convenience of non-

Swedish speakers there is a CD .pdf version, containing both English and Swedish texts,

available singly.

The CD contains all of the content of the printed version, including photographs and

illustrations (some in color), but there may be some variation in the pagination of the two

versions, thus affecting the index, which is keyed to the print version. Also it should be

noted that the author, Ingemar Wågerman, provided the English translation, and he states

that his “literal translation is not [always] idiomatically correct.” There are, indeed, some

such errors of idiom, but they are minor, none actually impeding communication.]

350 SEK (book and CD), 200 SEK (CD only); prices include postage.

Exploring the relationship between jazz and religion would be an ambitious, even immense,

undertaking, given the breadth of these two subjects; it would involve countless hours of

research of both primary and secondary sources; and it would result in several volumes. So

Wågerman, who hails from Sweden and is the pianist and leader of a New Orleans-style jazz

band called the Göta River Jazzmen, sensibly restricts it for the most part to the relationship

between traditional (i.e, early) jazz and religion, mainly Christianity, eschewing the more

modern forms of jazz and non-Christian religions other than to give them a passing

consideration.

His account centers on what Wågerman considers the defining event in the relationship of

jazz and religion—the George Lewis band’s performance at Holy Trinity Episcopal Church,

Oxford, Ohio, on Mar. 22, 1953, where for perhaps the first time the music of an entire church

service was provided by a jazz band. The following year this event was repeated and

recorded, resulting in the Lewis band album “Jazz at Vespers,” which the author adopts as

his title for this treatise.

Wågerman begins by tracing the development of the gospels, spirituals, and blues in the

music of the Christian church in the United States, particularly that of the Baptist and

Pentecostal denominations, from the early 19th century up to the traditional jazz “revival”

that occurred ca. 1940. He discusses the opposition to jazz music in the first half of the 20th

century by many in the church as well as the acceptance, albeit limited, by others, and he

assiduously pursues every recording he can locate which gives evidence of jazz bands’

playing music usually found only in church, such as the Morgan band’s 1927 seminal

recordings of “Sing On,” “Down by the Riverside,” and “Over in the Gloryland.” He also

quotes extensively what musicians had to say about the subject, and he gives the same close

attention to the jazz recordings issued during the revival period and from then to the

present.

Not limiting the scope to the U.S. only, he considers the traditional jazz being played non-

Swedes as native Sweden, as one might expect. Perhaps this section will be of least appeal to

they will have little familiarity with the musical milieu in that part of the world. non-

Wågerman’s observations about the relationship of religion and jazz are often provocative: for

instance, traditional jazz musicians do not, for the most part, compose new songs in the

idiom but adopt those already extant—gospels, spirituals, hymns—and “jazz” them; whereas

more modern jazz musicians, such as Ellington, Mingus, Brubeck, compose new works with a

religious subject. (It might also be added that the author believes that the influence of non-

Christian religions, such as Islam or Buddhism, on jazz is minor and mainly to be found in

“modern” jazz.)

Another interesting tenet he advances is that brass bands played an important part in

bringing jazz and religion together. He examines both the European and West African roots

of the New Orleans brass bands, noting how these became manifest in the New Orleans

funeral. From the European came the funereal dirge on the way to the cemetery; from the

West African came the singing and dancing following the interment that became the second

line. In turn the music flowed both ways, religious pieces such as “Just a Closer Walk” being

included in bands’ repertoires on secular occasions, and profane pieces such as “I’ll be Glad

When You’re Dead” being played as the bands stomped their way back from the cemetery.

As stated above, much of the book centers on the importance of the role the revivalists, such

as Bunk Johnson and George Lewis, played in influencing the adoption of religious songs

into jazz and the acceptance of jazz into the liturgy of the church, and Wågerman provides an

illuminating analysis of it.

The book also provides an exhaustive list of tunes—and often their lyrics—that comprise this

repertoire, with an extended analysis of one of his favorites, “Lily of the Valley,” and

another of that jazz anthem “When the Saints Go Marching In.” Another list supplies data

on albums of religious-oriented traditional jazz. (Band leaders or musical directors would

undoubtedly find this section of the book of considerable utility.) Finally, there is an

extensive bibliography appended. All of this attests to the painstaking research Wågerman

conducted, resulting in a book that, while not being perhaps definitive in every area, is very

enlightening and persuasive on the whole subject of the relationship of jazz and religion.

One can obtain more information at the web site www.jazzhistoria.se or by e-mail from

jazzhistoria@gmail.com.

|

|